Last winter was hard. It seemed like we didn't see the sun for several weeks, just a vague brightening of the sky as snow fell each day. It was cold, it was grey, it was hard to get around. It weighed on me, like a stone I carried each day as I cleared that day's inches of snow from my driveway.

It was, of course, impermanent, as weather always is. The sun came out; spring arrived, then summer.

But as the days got shorter in October, I felt my anxiety ramp up. The late afternoon darkness was back. I tensed, anticipating the weight of winter. My friend, a Buddhist teacher, suggested I flip my thinking, starting with noticing things I like about November.

That led me to examine my attitude toward winter in general. Instead of dreading the darkness, could I embrace it? Without becoming a Pollyanna who believes the pile of shit must indicate the presence of a pony nearby -- and surely one meant just for me! -- could I at least muster up equanimity about the advancing winter?

Could I learn to love the darkness?

In the bardo, there's not only the experience of light but of darkness. I've meditated on the light, on recognizing that as the ground of being, essential nature, but what about the dark? What about the absence of light? Could that also be a place of enlightenment? Endarkenment? Is there a difference between light and dark in emptiness?

Padampa Sangye advised Machig Labron:

Confess your hidden faults.

Approach what you find repulsive.

Help those you think you cannot help.

Anything you are attached to, give that.

Go to the places that scare you.

So I'm going to Iceland. In December. The sun rises at 11:11 a.m. It sets at 3:31 p.m. Four hours of sun. Twenty hours of dark.

I like to ponder potential tattoos. One of the things I

consider is a phrase from a chod practice I do: Enjoy everything without

attachment or aversion.

That's the intention. Enjoy the dark. Enjoy the light. Don't let enjoyment depend on external circumstances. Be the bliss.

Friday, December 11, 2015

Wednesday, September 30, 2015

Projectile defilements

While Pope Francis dominated the religious scene last week with his display of charm and compassion during visits to Washington, D.C., New York, and Philadelphia, His Holiness the Dalai Lama managed to cause a stir with his response to an interviewer's question about his possible successor.

Yes, HHDL said, of course the next Dalai Lama could be female. And, he added, pointing to his face, she should be attractive. The male interviewer was aghast. The Dalai Lama giggled. The video cuts to another question.

This is nothing new. HHDL has said for years that his mindstream might choose a female form next time around, maybe even a western woman. He's also said he won't come back. And the Chinese have said they'll find him.

And he's also said before that if his successor is a woman, she should be attractive. He points to his face. And giggles.

The interviewers' reactions seem to have more to do with their perceptions than his words -- ie, "You can't say that." Well, no, white male western interviewer, you can't say that because we have a pretty good idea of what you mean by it -- that looks matter more than wisdom. We don't know what HHDL means by it because interviewers stop there. I wish they wouldn't.

Maybe it's a joke -- she should be attractive like me, says the wizened monk. Maybe it's a reference to the padma, or magnetizing, energy a spiritual leader needs. Maybe it's a great big cosmic joke because enlightened beings see beyond the dualities the rest of us use to measure our progress -- hope/fear, good/bad, attractive/repulsive.

The lesson for me -- which I'm always learning -- is that when someone says something I find offensive, before I jump on my high horse and ride off, I need to try to understand what they're saying. I don't need to agree with it, but I need to know more about what they mean. You think vaccines cause autism? Why? Because someone told you about their experience? Have you looked at the science? Are you open to considering it? No? Got it.

There's an often-repeated story about HHDL meeting with a group of western Buddhist teachers a few decades ago. Sharon Salzberg asked him about working with self-hatred. The Dalai Lama was puzzled -- he had no context for understanding that since it wasn't part of the Tibetan experience. Maybe he's not familiar with the pressure westerners feel to be attractive.

When I feel self-righteous, I've learned, I need to look at the self. What part of me is reacting? What is her story? Does it apply to the situation in this moment, or can I let that go and see the situation differently, with more clarity?

We have a tendency to project our strongest defilements onto others. I listened to a talk today in which Matthew Brensilver, a teacher with Against the Stream, describes how our habitual reactions come out in stark clarity in retreat. We can become intensely angry, he says, that the kitchen has used the wrong beans, garbanzo beans!, when clearly the salsa-like dressing on the salad called for kidney beans. It's funny, but so true. We can be triggers looking for a target.

Surprisingly, to me, I'm not feeling righteous about HHDL's comment. Before he said he wants to be attractive in his next life, he expressed surprise that anyone would be surprised that a woman could be the leader of a Tibetan Buddhist lineage. It's happened before, he says, centuries ago. Why not again? There are many wise women teaching Tibetan Buddhism -- if that's what you need to feel like you belong here, find one of them. Or do you have issues with a woman teacher?

On a side note, the Dalai Lama has been advised by his doctors in the US to rest, to cancel a planned tour. He's 80, and his human body is aging, as all of our bodies do. I imagine that no one is better prepared for death than he is, but his death will create complications for Tibet and Tibetan Buddhists and the world. May he rest and recover and remain to teach for a long time. May we spend more energy following his example and teachings and less bickering over his words.

Yes, HHDL said, of course the next Dalai Lama could be female. And, he added, pointing to his face, she should be attractive. The male interviewer was aghast. The Dalai Lama giggled. The video cuts to another question.

This is nothing new. HHDL has said for years that his mindstream might choose a female form next time around, maybe even a western woman. He's also said he won't come back. And the Chinese have said they'll find him.

And he's also said before that if his successor is a woman, she should be attractive. He points to his face. And giggles.

The interviewers' reactions seem to have more to do with their perceptions than his words -- ie, "You can't say that." Well, no, white male western interviewer, you can't say that because we have a pretty good idea of what you mean by it -- that looks matter more than wisdom. We don't know what HHDL means by it because interviewers stop there. I wish they wouldn't.

Maybe it's a joke -- she should be attractive like me, says the wizened monk. Maybe it's a reference to the padma, or magnetizing, energy a spiritual leader needs. Maybe it's a great big cosmic joke because enlightened beings see beyond the dualities the rest of us use to measure our progress -- hope/fear, good/bad, attractive/repulsive.

The lesson for me -- which I'm always learning -- is that when someone says something I find offensive, before I jump on my high horse and ride off, I need to try to understand what they're saying. I don't need to agree with it, but I need to know more about what they mean. You think vaccines cause autism? Why? Because someone told you about their experience? Have you looked at the science? Are you open to considering it? No? Got it.

There's an often-repeated story about HHDL meeting with a group of western Buddhist teachers a few decades ago. Sharon Salzberg asked him about working with self-hatred. The Dalai Lama was puzzled -- he had no context for understanding that since it wasn't part of the Tibetan experience. Maybe he's not familiar with the pressure westerners feel to be attractive.

When I feel self-righteous, I've learned, I need to look at the self. What part of me is reacting? What is her story? Does it apply to the situation in this moment, or can I let that go and see the situation differently, with more clarity?

We have a tendency to project our strongest defilements onto others. I listened to a talk today in which Matthew Brensilver, a teacher with Against the Stream, describes how our habitual reactions come out in stark clarity in retreat. We can become intensely angry, he says, that the kitchen has used the wrong beans, garbanzo beans!, when clearly the salsa-like dressing on the salad called for kidney beans. It's funny, but so true. We can be triggers looking for a target.

Surprisingly, to me, I'm not feeling righteous about HHDL's comment. Before he said he wants to be attractive in his next life, he expressed surprise that anyone would be surprised that a woman could be the leader of a Tibetan Buddhist lineage. It's happened before, he says, centuries ago. Why not again? There are many wise women teaching Tibetan Buddhism -- if that's what you need to feel like you belong here, find one of them. Or do you have issues with a woman teacher?

On a side note, the Dalai Lama has been advised by his doctors in the US to rest, to cancel a planned tour. He's 80, and his human body is aging, as all of our bodies do. I imagine that no one is better prepared for death than he is, but his death will create complications for Tibet and Tibetan Buddhists and the world. May he rest and recover and remain to teach for a long time. May we spend more energy following his example and teachings and less bickering over his words.

Monday, September 14, 2015

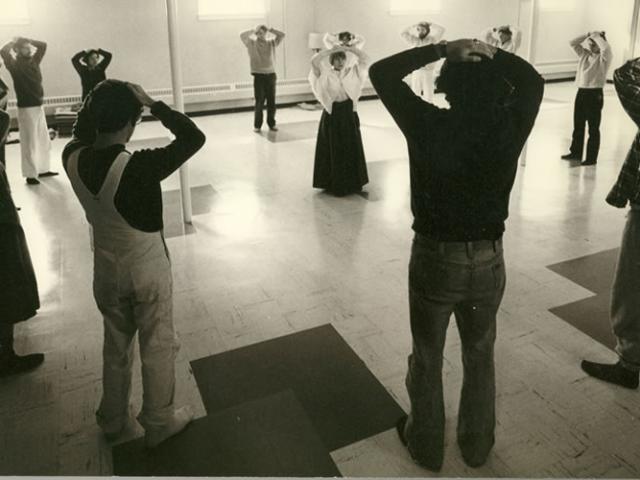

Off the cushion, on the dance floor

"It's a meditation," the dance instructor says, coaxing me to relax and follow him in the tango.

I immediately realize he's right -- or at least that tango requires me to bring my meditation training to the dance. Just before his comment, I'd been looking over his shoulder at the pairs of students moving around the studio, shifting my attention off my partner and his guidance. Wrong move. Like bringing my awareness back to my breath in shamata meditation, I bring my attention back to Jack, the instructor, back to this moment, this step, this gentle pressure that his palm exerts against mine, telling my body to pivot left.

Tango lessons are nowhere on my bucket list, but I'm visiting a dear friend who's just started and asks if I want to go with her. I can take the intro class and stay for the beginner class, if I'm inclined. After that we can go practice at nearby sushi restaurant that lets the tango-ers take over a back room that's under-used in the late afternoon.

I'm neutral on the tango, personally, but I'm delighted by her delight and willing to explore its spark. I've no personal investment in this -- if I somehow am unable to perform the duties of tango, I can sit on the side and watch. I love to watch dance, to observe bodies in space.

Why the tango? the instructor asks the three couples and me who are there for the rank beginner intro class (my friend opts for the more advanced technique side of the room). I'm just here with a friend, I say. I'm open to whatever the experience is. (That's meditation practice right there -- going in without hope or fear, free from attachment and aversion.)

And if it is a meditation, the tango is tantric meditation -- at least as I hear it explained by this instructor. It's less about following a set pattern of steps and more about sensing and playing with energy, he says. The leader doesn't push his partner into steps but feels her energy and uses that to guide her. It's a movement of active and receptive energy, subtle and silent, sensed rather than announced. It requires concentration and relaxation, stillness and movement. There's a leader and follower -- male and female, for this class -- but those roles are fluid; the leader actually follows the follower's energy; the follower guides the leader, taking languid pauses for a flip of the heel or a circle on the floor.

Most of all, it requires presence, the willingness to be there with the energy and let it flow. Try to anticipate, and you block the movement. Look around and compare yourself to others and stumble. It's only fun if you're doing only it.

And it is fun -- to take those attention-gathering skills off the cushion and bring them to the dance, to use them with bodies in motion -- and in relationship, not just in stillness. (I confess: I love the prostration part of my ngondro practice because of the physicality, a rare time when the body in the body-speech-mind triad gets to move.)

And if meditation training applies to tango lessons, maybe there are other, less exotic places

where it also can bring vibrancy and delight and an awareness of energies interacting, giving and receiving, guiding and following. Maybe we can be like the Padma deities in the Dechen Barwa, "magical dancers ... in the boundless net of illusion."

Maybe enlightenment is being able to tango with reality. Backwards, sometimes. And in glittery high heels.

I immediately realize he's right -- or at least that tango requires me to bring my meditation training to the dance. Just before his comment, I'd been looking over his shoulder at the pairs of students moving around the studio, shifting my attention off my partner and his guidance. Wrong move. Like bringing my awareness back to my breath in shamata meditation, I bring my attention back to Jack, the instructor, back to this moment, this step, this gentle pressure that his palm exerts against mine, telling my body to pivot left.

Tango lessons are nowhere on my bucket list, but I'm visiting a dear friend who's just started and asks if I want to go with her. I can take the intro class and stay for the beginner class, if I'm inclined. After that we can go practice at nearby sushi restaurant that lets the tango-ers take over a back room that's under-used in the late afternoon.

I'm neutral on the tango, personally, but I'm delighted by her delight and willing to explore its spark. I've no personal investment in this -- if I somehow am unable to perform the duties of tango, I can sit on the side and watch. I love to watch dance, to observe bodies in space.

Why the tango? the instructor asks the three couples and me who are there for the rank beginner intro class (my friend opts for the more advanced technique side of the room). I'm just here with a friend, I say. I'm open to whatever the experience is. (That's meditation practice right there -- going in without hope or fear, free from attachment and aversion.)

And if it is a meditation, the tango is tantric meditation -- at least as I hear it explained by this instructor. It's less about following a set pattern of steps and more about sensing and playing with energy, he says. The leader doesn't push his partner into steps but feels her energy and uses that to guide her. It's a movement of active and receptive energy, subtle and silent, sensed rather than announced. It requires concentration and relaxation, stillness and movement. There's a leader and follower -- male and female, for this class -- but those roles are fluid; the leader actually follows the follower's energy; the follower guides the leader, taking languid pauses for a flip of the heel or a circle on the floor.

Most of all, it requires presence, the willingness to be there with the energy and let it flow. Try to anticipate, and you block the movement. Look around and compare yourself to others and stumble. It's only fun if you're doing only it.

And it is fun -- to take those attention-gathering skills off the cushion and bring them to the dance, to use them with bodies in motion -- and in relationship, not just in stillness. (I confess: I love the prostration part of my ngondro practice because of the physicality, a rare time when the body in the body-speech-mind triad gets to move.)

And if meditation training applies to tango lessons, maybe there are other, less exotic places

where it also can bring vibrancy and delight and an awareness of energies interacting, giving and receiving, guiding and following. Maybe we can be like the Padma deities in the Dechen Barwa, "magical dancers ... in the boundless net of illusion."

Maybe enlightenment is being able to tango with reality. Backwards, sometimes. And in glittery high heels.

Wednesday, August 26, 2015

What's discipline got to do with it?

I hate Dallas. I hate Dallas with a fiery hate equal to the temperature on this August afternoon outside the terminal at Love Field where I'm waiting for an airport-to-hotel shuttle.

I hate Dallas. That's a broad statement, but it's the kind of thing I tend to say, consigning an entire city or category of things to the trash bin of "unpleasant experience." Tofu. Humidity. Feta cheese.

And I don't mean it. It's what Tsoknyi Rinpoche calls "real, but not true." If I look closely at the causes and conditions that give rise to the thought "I hate Dallas," what is there is not a concrete lump of hate for a whole city but discomfort with being hot, hungry, unsure of what will happen next.

Waiting.

Transitioning,

The groundlessness of being in a space that's neither here nor there.

I want to be back at the retreat center I left a few hours earlier. I want to be home with my spouse. I just don't want to be in a 16-hour layover at Dallas-Forth Worth airport, waiting for a shuttle.

I'd been reading Tsoknyi Rinpoche's "Open Heart Open Mind" on the plane that brought me to Dallas, and I'd just read a section on how to work with difficult people. Rinpoche's one-word prescription: Discipline.

It takes discipline, one of the paramitas -- or perfections of the heart -- to stay with the difficult feelings, to accept that they are your feelings, and to see them as the impermanent, ephemeral things they are instead of treating them like a slab of marble, carving a statue, and writing a story that's engraved on a plaque to justify the whole thing.

I don't hate Dallas. I dislike how I feel at the moment, when I happen to be in Dallas.

When I see that, I see space around my feelings, space in which I know everything will be OK. The shuttle will come or I'll walk upstairs and get a cab. The hotel will be air-conditioned. I'll find food.

It's a similar process in working with a difficult person in metta meditation. When you tease out your feelings about this person, about their behavior, from the human being, you can see that they are just getting through the day. It becomes easier to send lovingkindness -- the wish that they will be safe, happy, healthy, and live with ease -- when you see them as human rather than a monument to their irritating qualities. You don't have to like them or what they do, just see their humanity. Address yourself to their humanity, not their irritating qualities. You may find those qualities become less important and less irritating.

And then you can rest in that space, finding comfort wherever you are.

I hate Dallas. That's a broad statement, but it's the kind of thing I tend to say, consigning an entire city or category of things to the trash bin of "unpleasant experience." Tofu. Humidity. Feta cheese.

And I don't mean it. It's what Tsoknyi Rinpoche calls "real, but not true." If I look closely at the causes and conditions that give rise to the thought "I hate Dallas," what is there is not a concrete lump of hate for a whole city but discomfort with being hot, hungry, unsure of what will happen next.

Waiting.

Transitioning,

The groundlessness of being in a space that's neither here nor there.

I want to be back at the retreat center I left a few hours earlier. I want to be home with my spouse. I just don't want to be in a 16-hour layover at Dallas-Forth Worth airport, waiting for a shuttle.

I'd been reading Tsoknyi Rinpoche's "Open Heart Open Mind" on the plane that brought me to Dallas, and I'd just read a section on how to work with difficult people. Rinpoche's one-word prescription: Discipline.

It takes discipline, one of the paramitas -- or perfections of the heart -- to stay with the difficult feelings, to accept that they are your feelings, and to see them as the impermanent, ephemeral things they are instead of treating them like a slab of marble, carving a statue, and writing a story that's engraved on a plaque to justify the whole thing.

I don't hate Dallas. I dislike how I feel at the moment, when I happen to be in Dallas.

When I see that, I see space around my feelings, space in which I know everything will be OK. The shuttle will come or I'll walk upstairs and get a cab. The hotel will be air-conditioned. I'll find food.

It's a similar process in working with a difficult person in metta meditation. When you tease out your feelings about this person, about their behavior, from the human being, you can see that they are just getting through the day. It becomes easier to send lovingkindness -- the wish that they will be safe, happy, healthy, and live with ease -- when you see them as human rather than a monument to their irritating qualities. You don't have to like them or what they do, just see their humanity. Address yourself to their humanity, not their irritating qualities. You may find those qualities become less important and less irritating.

And then you can rest in that space, finding comfort wherever you are.

Labels:

Dallas,

DFW,

difficult emotions,

difficult person,

layover,

metta,

paramitas,

Tsoknyi Rinpoche

Friday, August 7, 2015

I love you anyway

Very early tomorrow I will be getting on a plane and heading off to a fairly remote retreat center in Colorado. Very early. The first flight leaves at 5 a.m., which means leaving the house around 2:30 a.m. to allow for check-in and security and all that.

I made the arrangements a while back. Lots of life has happened since then and I forgot what I'd booked. When I looked up my travel arrangements this week, my immediate reaction was, "What fool booked these flights?" Of course, it was me. And of course there were reasons -- cost, check-in time, etc.

At those moments, when my first reaction is to speak harshly to myself, I am reminded of a story Sharon Salzberg tells in "Lovingkindess." She'd been practicing metta meditation for a while but wasn't sure it was having an effect. Then one day she broke a glass and heard the automatic voice of her self talk, "You're such a klutz." And then the voice of metta spoke up: "And I love you."

Practicing metta meditation doesn't run you into a bowl of mush. It doesn't necessarily stop the voices of habit in your head. It does add the coda: "And I love you." Yeah, sometimes you make bad decisions, sometimes you don't pay attention, sometimes you mess up. And I love you.

You come to believe that you are loveable. And if you are loveable, even with your annoying habits, others are too.

I made the arrangements a while back. Lots of life has happened since then and I forgot what I'd booked. When I looked up my travel arrangements this week, my immediate reaction was, "What fool booked these flights?" Of course, it was me. And of course there were reasons -- cost, check-in time, etc.

At those moments, when my first reaction is to speak harshly to myself, I am reminded of a story Sharon Salzberg tells in "Lovingkindess." She'd been practicing metta meditation for a while but wasn't sure it was having an effect. Then one day she broke a glass and heard the automatic voice of her self talk, "You're such a klutz." And then the voice of metta spoke up: "And I love you."

Practicing metta meditation doesn't run you into a bowl of mush. It doesn't necessarily stop the voices of habit in your head. It does add the coda: "And I love you." Yeah, sometimes you make bad decisions, sometimes you don't pay attention, sometimes you mess up. And I love you.

You come to believe that you are loveable. And if you are loveable, even with your annoying habits, others are too.

Saturday, August 1, 2015

Meeting meanness with metta

I don't have to tell you that the world is a mean place. You know that -- you're on the Internet, which some days seems like nothing more than a place to share hatred and rage and stories of the awful way people treat other beings. It can feel overwhelming.

What can you do when faced with a tide of aggression and ignorance?

Practice lovingkindness.

Lovingkindness -- often known by its Pali word, metta -- is a quality of friendliness, "a steady, unconditional sense of connection that touches all beings, without exception, including ourselves," according to Sharon Salzberg, a Buddhist teacher who literally wrote the book on loving-kindness 20 years ago.

I love that her book calls lovingkindness "the revolutionary art of happiness." Kindness, it seems, is directed outward, toward others. We do kind things for other beings. And yet we reap the benefits.

In lovingkindness meditation, we make the aspiration that several categories of beings (ourselves, a mentor, a loved one, a neutral person, a difficult person, a group, and all beings) experience happiness, health, freedom, and ease. We don't necessarily take action, just make the aspiration.

But thought is precursor to action. As the Buddha said, "With our thoughts we make the world." So if we see the world as filled with hate and aggression that threatens us, we react defensively. If we aspire to keep people a safe distance away from us, we don't create the connections we innately crave and need to have in order to thrive.

If we practice sending out kind thoughts in meditation, we begin to send out kind thoughts outside of meditation.

Last month I was coming home from a meditation retreat in Colorado, and I met the nicest people all along my two-airplane, multihour trip -- from the shuttle bus driver who talked about the herds of rabbits that live along the airport access road in Albuquerque to the woman who commented on my giant cinnamon bun to the other people squeezed into the second-to-last row of the plane (who spread out once we realized no one had been condemned to sit in the last row).

Did I have extraordinary luck in the people I encountered that day? Nope. But I had spent a week cultivating kind intention, so I didn't take offense when a stranger remarked on unhealthy snack. I didn't write off the talkative man as a distracting loudmouth. I experienced it less defensively, as people looking to connect with other people in their own ways.

It's not always easy to maintain that view outside of retreat when you're actively working on that. But it is possible to make time to work on that. August is Metta Month at the Interdependence Project; there are many opportunities to practice together in real life and online.

Besides, metta meditation can be practiced steathily. On my way to retreat, I sat outside a Starbucks at Love Field in Dallas, silently wishing happiness and ease to the stressed-out passengers going by me. I don't expect it did anything for them, except put one less cranky person in their path, but it made my trip more pleasant. Try it.

|

| Image by dreamingphotographer.deviantart.com |

What can you do when faced with a tide of aggression and ignorance?

Practice lovingkindness.

Lovingkindness -- often known by its Pali word, metta -- is a quality of friendliness, "a steady, unconditional sense of connection that touches all beings, without exception, including ourselves," according to Sharon Salzberg, a Buddhist teacher who literally wrote the book on loving-kindness 20 years ago.

I love that her book calls lovingkindness "the revolutionary art of happiness." Kindness, it seems, is directed outward, toward others. We do kind things for other beings. And yet we reap the benefits.

In lovingkindness meditation, we make the aspiration that several categories of beings (ourselves, a mentor, a loved one, a neutral person, a difficult person, a group, and all beings) experience happiness, health, freedom, and ease. We don't necessarily take action, just make the aspiration.

But thought is precursor to action. As the Buddha said, "With our thoughts we make the world." So if we see the world as filled with hate and aggression that threatens us, we react defensively. If we aspire to keep people a safe distance away from us, we don't create the connections we innately crave and need to have in order to thrive.

If we practice sending out kind thoughts in meditation, we begin to send out kind thoughts outside of meditation.

Last month I was coming home from a meditation retreat in Colorado, and I met the nicest people all along my two-airplane, multihour trip -- from the shuttle bus driver who talked about the herds of rabbits that live along the airport access road in Albuquerque to the woman who commented on my giant cinnamon bun to the other people squeezed into the second-to-last row of the plane (who spread out once we realized no one had been condemned to sit in the last row).

Did I have extraordinary luck in the people I encountered that day? Nope. But I had spent a week cultivating kind intention, so I didn't take offense when a stranger remarked on unhealthy snack. I didn't write off the talkative man as a distracting loudmouth. I experienced it less defensively, as people looking to connect with other people in their own ways.

It's not always easy to maintain that view outside of retreat when you're actively working on that. But it is possible to make time to work on that. August is Metta Month at the Interdependence Project; there are many opportunities to practice together in real life and online.

Besides, metta meditation can be practiced steathily. On my way to retreat, I sat outside a Starbucks at Love Field in Dallas, silently wishing happiness and ease to the stressed-out passengers going by me. I don't expect it did anything for them, except put one less cranky person in their path, but it made my trip more pleasant. Try it.

Saturday, July 25, 2015

Make a wish

My mom recently heard about an organization that grants senior citizens' wishes, like those groups that send terminally ill children and their families to Disney World, but this was for regular seniors with no special issues. This led her to think about what she'd wish for, she told me.

Her first thought was a trip across the country to visit my aunt. Sadly, the wish-granting organization is bound by the laws of time and space, and she'd still have to undergo the actual travel, which is what's holding her back. She dislikes airplanes, and other methods would take too long (otherwise I, her daughter, could grant this wish). No tesseract, no travel.

So then she thought that she'd like to revisit our family vacations in Cape Cod. But again the organization lacked the capacity to take everyone back 20 years when the grandkids would be happy hunting hermit crabs and digging holes for hours on end while she doled out Twizzlers.

She decided she didn't really have a grant-able wish, so she would simply be happy with how things are. She's a wise woman.

Our conversation made me think, though, of how often our hopes and wishes and expectations -- conscious and especially unconscious -- would crumble under the light of awareness. Do we realize how much our good mood depends on the weather cooperating or our co-worker's mood or the arrival of an anticipated email? How much we expect consistency from our technology and environment and friends? How much we are thrown off balance when we don't get that?

We pin our happiness on achieving some ideal situation, big or small -- the dishwasher will be empty when we open it; we'll find a well-paying, fulfilling job that benefits society; the tomatoes will have ripened overnight. And if that doesn't happen, we're disgruntled at having to empty the dishwasher or answer phones cheerfully or eat plain salad.

We fail to see what we have, right now, because we thought it would be different.

But we can change that.

Her first thought was a trip across the country to visit my aunt. Sadly, the wish-granting organization is bound by the laws of time and space, and she'd still have to undergo the actual travel, which is what's holding her back. She dislikes airplanes, and other methods would take too long (otherwise I, her daughter, could grant this wish). No tesseract, no travel.

So then she thought that she'd like to revisit our family vacations in Cape Cod. But again the organization lacked the capacity to take everyone back 20 years when the grandkids would be happy hunting hermit crabs and digging holes for hours on end while she doled out Twizzlers.

She decided she didn't really have a grant-able wish, so she would simply be happy with how things are. She's a wise woman.

Our conversation made me think, though, of how often our hopes and wishes and expectations -- conscious and especially unconscious -- would crumble under the light of awareness. Do we realize how much our good mood depends on the weather cooperating or our co-worker's mood or the arrival of an anticipated email? How much we expect consistency from our technology and environment and friends? How much we are thrown off balance when we don't get that?

We pin our happiness on achieving some ideal situation, big or small -- the dishwasher will be empty when we open it; we'll find a well-paying, fulfilling job that benefits society; the tomatoes will have ripened overnight. And if that doesn't happen, we're disgruntled at having to empty the dishwasher or answer phones cheerfully or eat plain salad.

We fail to see what we have, right now, because we thought it would be different.

But we can change that.

Monday, July 20, 2015

What has Buddhism done for you?

I was fortunate to spend a week this month on retreat with a teacher who had kickstarted my personal exploration of the Buddhist path a few years ago. By then, I'd been studying Buddhism for a while, but it had been largely intellectual until I did a weekend program with him, and later a weeklong retreat.

Since then I've seen him mostly for weekend programs and kept up with his podcasts and books. Sitting with him again in person was a push my practice needed -- and an opportunity for reflection on where I am and where I had been.

"Buddhism saved my life," I told him one evening after a session where several people shared their stories. (This was a retreat that emphasized building sangha; we were silent for half the day and spoke during the other half.)

Maybe I was being dramatic. Maybe not. Buddhism definitely helped me see and change negative patterns of thinking. It let me be touched by joy as well as suffering, to see the inseparability of the two. Suffering exists; it feels good to admit that, to not try to talk my way out of that. It arises from causes and conditions. It can be eased.

Today, July 20, is celebrated in Tibetan Buddhism as Chokhor Duchen, the anniversary of the Buddha's first teaching, which was on the Four Noble Truths. This is also known as the first turning of the wheel of dharma.

I am personally deeply grateful for the teachings, those who teach them, and those who study them. My all beings everywhere without one exception benefit.

Since then I've seen him mostly for weekend programs and kept up with his podcasts and books. Sitting with him again in person was a push my practice needed -- and an opportunity for reflection on where I am and where I had been.

"Buddhism saved my life," I told him one evening after a session where several people shared their stories. (This was a retreat that emphasized building sangha; we were silent for half the day and spoke during the other half.)

Maybe I was being dramatic. Maybe not. Buddhism definitely helped me see and change negative patterns of thinking. It let me be touched by joy as well as suffering, to see the inseparability of the two. Suffering exists; it feels good to admit that, to not try to talk my way out of that. It arises from causes and conditions. It can be eased.

Today, July 20, is celebrated in Tibetan Buddhism as Chokhor Duchen, the anniversary of the Buddha's first teaching, which was on the Four Noble Truths. This is also known as the first turning of the wheel of dharma.

I am personally deeply grateful for the teachings, those who teach them, and those who study them. My all beings everywhere without one exception benefit.

Saturday, June 20, 2015

All beings tremble

All beings tremble before violence.

All fear death.

All love life.

See yourself in others.

Then whom can you hurt?

What harm can you do?

-The Dhammapada

Suffering arises when we see our selves as separate -- from the initial moment when our consciousness is aware of itself and mistakenly thinks that means it is separate from the ground of being rather than the truth, that it is an expression of the ground. Suffering is intensified when we solidify our selves and see them as separate from other selves, when we see others as a threat, when we think -- not that they love life and fear death, just like us -- that they want to harm us. We become guarded and defensive, maybe aggressive because we think it's better to avoid the threat by eliminating what we think is the source than to wait and see if the perceived threat is real.

Suffering is reduced when we see our interdependence, recognizing that we all have the same nature -- which is the same nature of the ground of being.

When I hear the words of the families of those killed at Emanuel American Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, spoken to Dylann Roof, the man who murdered them, I hear the grace that comes from that recognition. Speaking in court, while Roof was held in jail and listened over a video feed, they offered forgiveness.

"I will never be able to hold her again, but I forgive you," a daughter of Ethel Lance said. "And have mercy on your soul. You hurt me. You hurt a lot of people but God forgives you, and I forgive you."

I hear sadness and pain, but not anger and righteous, not defensiveness and isolation. We are all one in God, the families of those murdered at a prayer service said, and God, not us, will judge you.

Not like Dylann Roof judged them. Judgment creates separation, isolation, suffering. It closes us down. Interdependence opens us up, lets us witness the separation and take action to overcome it.

All fear death.

All love life.

See yourself in others.

Then whom can you hurt?

What harm can you do?

-The Dhammapada

Suffering arises when we see our selves as separate -- from the initial moment when our consciousness is aware of itself and mistakenly thinks that means it is separate from the ground of being rather than the truth, that it is an expression of the ground. Suffering is intensified when we solidify our selves and see them as separate from other selves, when we see others as a threat, when we think -- not that they love life and fear death, just like us -- that they want to harm us. We become guarded and defensive, maybe aggressive because we think it's better to avoid the threat by eliminating what we think is the source than to wait and see if the perceived threat is real.

Suffering is reduced when we see our interdependence, recognizing that we all have the same nature -- which is the same nature of the ground of being.

When I hear the words of the families of those killed at Emanuel American Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, spoken to Dylann Roof, the man who murdered them, I hear the grace that comes from that recognition. Speaking in court, while Roof was held in jail and listened over a video feed, they offered forgiveness.

"I will never be able to hold her again, but I forgive you," a daughter of Ethel Lance said. "And have mercy on your soul. You hurt me. You hurt a lot of people but God forgives you, and I forgive you."

I hear sadness and pain, but not anger and righteous, not defensiveness and isolation. We are all one in God, the families of those murdered at a prayer service said, and God, not us, will judge you.

Not like Dylann Roof judged them. Judgment creates separation, isolation, suffering. It closes us down. Interdependence opens us up, lets us witness the separation and take action to overcome it.

Good and evil exist on the same plane, and operate by the same calculus. Evil is good covered over. Wherever we ourselves, in our confusion and in our unwillingness to look at life as it actually is, with all its pain and difficulty, commit acts of evil, we add to the covering. And whenever we have the courage and the calmness to be with life as it is, and therefore, inevitably, to do good, then we remove the cover. We transform evil into good. This is the human capacity. Evil is not a part of reality that can be excised, cast out and overcome. Evil is a constant part of our world because there is only one world, there is only one life, and all of us share in it.

Norman FIscher, writing after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon

Thursday, June 4, 2015

Is One Direction all together in a Pure Land?

Buddhism is often seen these days as a supremely rational philosophical system or belief system, depending on your stance. Investigate everything, the Buddha said. Do not believe anything just because I tell you it is so -- look into it for yourselves and see whether it is.

For 2,600 years, people have been doing that and discovering the Middle Way he described does work.

So how do we explain vajrayana Buddhism, with its tantric practices, with its deities and devotion, its study of unmeasured energies?

You can see it as a way of training the subtle mind, using archetypal figures to cultivate certain qualities in ourselves -- compassion from Tara and Avaloketeshvara, wisdom from Prajna Paramita, clarity from Vajrasattva. You can explain its effects by analyzing its symbolism, icons, practices.

There's support for the idea that it's not just folklore from no less than Stephen Hawking.

In a Q&A after a recent lecture -- presented in Australia by a hologram of Hawking, who was physically in England -- he was asked: "What do you think is the cosmological effect of Zayn leaving One Direction and consequently breaking the hearts of millions of teenage girls across the world?"

The legendary physicist replied:

“My

advice to any heartbroken young girl is to pay close attention to the

study of theoretical physics. Because one day there may well be proof of

multiple universes.

“It would not be beyond the realms of possibility that somewhere outside of our own universe lies another different universe.

“And in that universe, Zayn is still in One Direction.”

So it's not out of the question that Pure Lands exist and may even be overlays onto our own world, or that Tara in one of her 21 manifestations can help us out, when supplicated.

For 2,600 years, people have been doing that and discovering the Middle Way he described does work.

So how do we explain vajrayana Buddhism, with its tantric practices, with its deities and devotion, its study of unmeasured energies?

You can see it as a way of training the subtle mind, using archetypal figures to cultivate certain qualities in ourselves -- compassion from Tara and Avaloketeshvara, wisdom from Prajna Paramita, clarity from Vajrasattva. You can explain its effects by analyzing its symbolism, icons, practices.

There's support for the idea that it's not just folklore from no less than Stephen Hawking.

In a Q&A after a recent lecture -- presented in Australia by a hologram of Hawking, who was physically in England -- he was asked: "What do you think is the cosmological effect of Zayn leaving One Direction and consequently breaking the hearts of millions of teenage girls across the world?"

The legendary physicist replied:

“Finally, a question about something important.

“It would not be beyond the realms of possibility that somewhere outside of our own universe lies another different universe.

“And in that universe, Zayn is still in One Direction.”

So it's not out of the question that Pure Lands exist and may even be overlays onto our own world, or that Tara in one of her 21 manifestations can help us out, when supplicated.

Labels:

buddhism,

effect of broken hearts,

hologram,

one direction,

stephen hawking,

tantra,

Tara,

vajrayana,

zayn

Saturday, May 30, 2015

Bisy backson

I've been writing for the IDP blog on a regular basis for almost five years -- not because I think I

have great insights to share but because it needs to be done. I've

worked on daily newspapers for all of my adult life (except for six

horrible months immediately after graduating from college when I did

public relations), and I understand the need for new content. I know how

to produce content. So I do.

For me, it's been a practice in opening, sharing ideas. Since I don't have a live, in-person sangha, this has been a way to explore ideas and share thoughts. It's also about discipline and posting on Saturday mornings. And I've been good about meeting that deadline, providing content. Until recently.

Over the last month or so, I've left my slot empty or posted at other times. There were good reasons: Travel, retreat, events. I've been too busy.

It's interesting that in Buddhism, busyness is associated with both laziness and restlessness. In both instances, external activity is a way to avoid facing what's happening internally.

Gil Fronsdal, talking about the hindrance of restlessness, says:

In the Samyutta Nikaya, the Buddha said that when the mind is restless, "it is the proper time for cultivating the following factors of enlightenment: tranquility, concentration, and equanimity, because an agitated mind can easily be quietened by them."

A time of restlessness is not the time for study because that can cause further excitement, he said.

But you can study the restless body and mind. Focus on the sensations; get to know, intimately, the feeling of restlessness, without the narration the mind provides. Feel the muscles, the energy, the tension and release. Then look at the mind: Where is the razor's edge, the head of the pin, the moment where you go from awareness to I-can't-stand-this-for-another-second? Can you find it? Can you rest there?

Feelings become overwhelming when the physical sensation and the mind work together to keep the hamster wheel of samsara spinning. You can investigate either one on its own, but when they join they create a tsunami of restlessness/busyness/stress that sucks you under.

As much as I identify with that scenario, that hasn't been the case for me lately. I'm not overwhelmed, just short on time. I have a job, a commitment to Buddhist practice that takes 2-3 hours a day, a family.

For some people, establishing discipline is a hard practice. That hasn't been my problem. Meditation has been a daily practice for me since I started. For me, not meeting expectations is much harder because it means giving up the validation that comes with doing what you're supposed to do. It means relying on myself to validate that I'm doing what's right for me. That's hard.

And then that's what you sit with.

For me, it's been a practice in opening, sharing ideas. Since I don't have a live, in-person sangha, this has been a way to explore ideas and share thoughts. It's also about discipline and posting on Saturday mornings. And I've been good about meeting that deadline, providing content. Until recently.

Over the last month or so, I've left my slot empty or posted at other times. There were good reasons: Travel, retreat, events. I've been too busy.

It's interesting that in Buddhism, busyness is associated with both laziness and restlessness. In both instances, external activity is a way to avoid facing what's happening internally.

Gil Fronsdal, talking about the hindrance of restlessness, says:

The traditional antidote for restlessness is to sit still.

Constant activity can channel the restlessness at the expense of neither confronting it nor settling it. Because restlessness is uncomfortable, it can be difficult to pay attention to. Paradoxically, restlessness is itself sometimes a symptom of not being able to be present for discomfort. Patience, discipline, and courage are needed to sit still and face it.

In the Samyutta Nikaya, the Buddha said that when the mind is restless, "it is the proper time for cultivating the following factors of enlightenment: tranquility, concentration, and equanimity, because an agitated mind can easily be quietened by them."

A time of restlessness is not the time for study because that can cause further excitement, he said.

But you can study the restless body and mind. Focus on the sensations; get to know, intimately, the feeling of restlessness, without the narration the mind provides. Feel the muscles, the energy, the tension and release. Then look at the mind: Where is the razor's edge, the head of the pin, the moment where you go from awareness to I-can't-stand-this-for-another-second? Can you find it? Can you rest there?

Feelings become overwhelming when the physical sensation and the mind work together to keep the hamster wheel of samsara spinning. You can investigate either one on its own, but when they join they create a tsunami of restlessness/busyness/stress that sucks you under.

As much as I identify with that scenario, that hasn't been the case for me lately. I'm not overwhelmed, just short on time. I have a job, a commitment to Buddhist practice that takes 2-3 hours a day, a family.

For some people, establishing discipline is a hard practice. That hasn't been my problem. Meditation has been a daily practice for me since I started. For me, not meeting expectations is much harder because it means giving up the validation that comes with doing what you're supposed to do. It means relying on myself to validate that I'm doing what's right for me. That's hard.

And then that's what you sit with.

Sunday, May 3, 2015

The ignorance of a depraved heart

The charge of "depraved heart murder" was filed against one of the Baltimore police officers accused in connection with the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore. That's an odd term for most of us: "Depraved heart."

Maybe it's more familiar as "depraved indifference."

"Depraved" is a strong and unusual word meaning morally corrupt and wicked. Most of us can look at this charge and assure ourselves that we're not capable of this act, we're not depraved.

But "indifferent." If being indifferent, or apathetic, is a crime, I know I'm guilty. We don't think of indifference as a problem in the course of the day. Maybe it makes life easier, sometimes, not to notice, not to care.

In Buddhism, the three poisons are passion, aggression, and ignorance. They keep the wheel of samsara spinning. It's easy to see with passion and aggression -- they're fiery, fierce, make themselves felt. Ignorance? Meh. How do we relate to what we don't know? How does ignorance -- or delusion -- cause suffering?

A few weeks ago, I attended a refuge vow ceremony with the Karmapa. Over the last decade, I've attended probably a dozen such ceremonies -- usually they leave you feeling warm and fuzzy, connected. Not this time.

Why, the Karmapa asked, would we go for refuge to the Buddha, the dharma, and the sangha -- the teacher, the teachings, and those who follow them? (Awareness, the paths that lead to awarness, and those who live in awareness.) Traditionally teachings cite two reasons: Fear and faith.

The Karmapa turned to another subtle and invisible danger: the inadequacy of our love. The fear of obvious dangers, such as war, famine or sickness, we can easily identify. Lack of love, however, is another story; it leaves too many people and animals without protection or refuge. Their terrible suffering could be prevented if we had enough love, His Holiness stated. Since this deficit is within us, we can recognize it and change, and change we must, as insufficient love poses not only the danger of eventual disaster for others but for ourselves as well.A deficit of love ...

Under the law, the charge of second-degree murder/ depraved heart requires "the conduct must contain an element of viciousness or contemptuous disregard for the value of human life which conduct characterizes that behavior as wanton."

The reason to take refuge, Karmapa said, is the fear of living in a world with insufficient love.

Usually, he said, we limit our love and compassion to relatives and friends; we set a boundary to our caring that allow us to ignore others.

“We need to extend our love,” the Karmapa said, “and come to see that we are connected to everyone.” The Karmapa expanded the usual definition of fear: “When we think about how living beings harm one another, we can see this lack of love clearly. Fearing it within ourselves, we go for refuge to develop the love and compassion that the Dharma teaches.”The opposite of compassion -- of seeing others' suffering and aspiring to remove it -- isn't hatred or aggression. It's apathy. Not seeing. Not caring.

What are the boundaries of your love and compassion? Who do you not see? Where is your love lacking? What are you indifferent to?

Love the questions, even when the answers are hard to find or hear. That's how boundaries expand. That's where change happens.

Labels:

depraved heart,

indifference,

insufficient love,

karmapa,

refuge,

three poisons

Friday, April 17, 2015

Compassion requires action

Compassion is the heart of the Buddhist teachings. The Dalai Lama, head of one of the lineages of Tibetan Buddhism and the face of Buddhism to much of the world, says that the purpose of life is to be happy, and the way to attain that is to develop compassion.

"The more we care for the happiness of others, the greater our own sense of well-being becomes. Cultivating a close, warm-hearted feeling for others automatically puts the mind at ease. This helps remove whatever fears or insecurities we may have and gives us the strength to cope with any obstacles we encounter. It is the ultimate source of success in life," he says.

Compassion is listed as one of the Brahma Viharas, or Divine Abodes, along with lovingkindness, empathetic joy, and equanimity. While lovingkindness is defined as the wish for all beings -- ourselves and others -- to be happy, compassion goes a step further, seeing suffering and aspiring to end it.

Looking deeply at others' suffering may sound depressing, but the Dalai Lama says it's what gives us the ability to face our difficulties without getting swamped:

Compassion develops on three levels: aspiring (we see others' suffering and wish it could be removed); active (we take action to alleviate the suffering); and absolute (we see no difference between ourselves and others, and every action we take is for the benefit of beings).

How do we develop compassion? We allow our hearts to be touched. Compassion is sometimes described as being tender-hearted -- it's the "aw" we feel watching cat videos on the Internet or looking at pictures of babies; the tears that fall when we hear another's pain; even the anger at injustice. (Using anger as skillful means is a topic all its own.) There are specific practices in which we imagine exchanging places with another person or taking their suffering into our own hearts and transforming it.

By developing an attitude of compassion -- of seeing suffering rather than ignoring or denying it or blaming the person who is suffering -- we behave differently in the world. That's important. That's world-changing.

The 17th Karmapa, head of another of the Tibetan Buddhist lineages, is touring the U.S. for three months and has spoken frequently about the need to act to protect the environment. Intellectual knowledge of the threat to the planet has not produced action because our heartfelt awareness, known as bodhicitta, hasn't kept pace. We care more for consumer goods than the Earth.

“The weakness of our compassion, and the weakness or outright lack of

our bodhicitta has placed this world in grave danger," he said. "We know this, it

is all around us and we are responsible for it. And yet we lack enough

compassion to care. We lack enough bodhicitta to do anything about it.

We need to work on that.”

Compassion depends on a personal, felt connection. When we act from that deep level, we respect the interdependent web of existence, cherishing all life as much as our own.

"The more we care for the happiness of others, the greater our own sense of well-being becomes. Cultivating a close, warm-hearted feeling for others automatically puts the mind at ease. This helps remove whatever fears or insecurities we may have and gives us the strength to cope with any obstacles we encounter. It is the ultimate source of success in life," he says.

Compassion is listed as one of the Brahma Viharas, or Divine Abodes, along with lovingkindness, empathetic joy, and equanimity. While lovingkindness is defined as the wish for all beings -- ourselves and others -- to be happy, compassion goes a step further, seeing suffering and aspiring to end it.

Looking deeply at others' suffering may sound depressing, but the Dalai Lama says it's what gives us the ability to face our difficulties without getting swamped:

As long as we live in this world we are bound to encounter problems. If, at such times, we lose hope and become discouraged, we diminish our ability to face difficulties. If, on the other hand, we remember that it is not just ourselves but every one who has to undergo suffering, this more realistic perspective will increase our determination and capacity to overcome troubles. Indeed, with this attitude, each new obstacle can be seen as yet another valuable opportunity to improve our mind!

Thus we can strive gradually to become more compassionate, that is we can develop both genuine sympathy for others' suffering and the will to help remove their pain. As a result, our own serenity and inner strength will increase.

Compassion develops on three levels: aspiring (we see others' suffering and wish it could be removed); active (we take action to alleviate the suffering); and absolute (we see no difference between ourselves and others, and every action we take is for the benefit of beings).

How do we develop compassion? We allow our hearts to be touched. Compassion is sometimes described as being tender-hearted -- it's the "aw" we feel watching cat videos on the Internet or looking at pictures of babies; the tears that fall when we hear another's pain; even the anger at injustice. (Using anger as skillful means is a topic all its own.) There are specific practices in which we imagine exchanging places with another person or taking their suffering into our own hearts and transforming it.

By developing an attitude of compassion -- of seeing suffering rather than ignoring or denying it or blaming the person who is suffering -- we behave differently in the world. That's important. That's world-changing.

The 17th Karmapa, head of another of the Tibetan Buddhist lineages, is touring the U.S. for three months and has spoken frequently about the need to act to protect the environment. Intellectual knowledge of the threat to the planet has not produced action because our heartfelt awareness, known as bodhicitta, hasn't kept pace. We care more for consumer goods than the Earth.

|

| His Holiness the 17th Karmapa plants a tree in New Haven. (Karmapaamerica.org) |

Compassion depends on a personal, felt connection. When we act from that deep level, we respect the interdependent web of existence, cherishing all life as much as our own.

Labels:

brahma viharas,

compassion,

Dalai Lama,

karmapa,

suffering

Sunday, April 12, 2015

Is Buddhism's rep for tolerance deserved?

A new study reports that merely reading Buddhist terms in a word puzzle -- such as dharma, Buddha, and awakening -- increased the likelihood of "prosocial" behaviors among study participants, some of them familiar with Buddhism and others not.

Testing the theory of "subliminal priming," researchers found that introducing language associated with Buddhism decreased explicit prejudice against ethnic, ideological, and moral groups other than those of the person. The results challenge the idea that religion promotes prosocial behavior among its members but prejudice toward those outside the group, the authors said. Prosocial behaviors include having compassion and empathy, along with a sense of responsibility for others.

That doesn't mean Buddhism is better, the authors stressed.

But after holding it for a while, I've decided that it's not untrue, either.

One of the beauties of Buddhism is that the Buddha doesn't mandate tolerance. He says, look into yourself and see what makes you intolerant. What makes you uncomfortable? Examine that -- if it is because the person is different, can you find areas of similarity? You both breathe, for starters. You both want to continue breathing. You both love things, maybe different things, but that feeling of love is the same. You're both humans in a confusing world. There's a common ground to start with, and if you dislike what the other person builds on that, you've still got that starting place to come back to so you can tolerate what does not harm your or the larger community and treat the other person with respect if you engage with them over their actions.

I saw this when I read a New York Times story about a woman who was asked to change her seat on an airplane because the man assigned to the seat next to her, an Orthodox Jew, was prohibited by his religion from sitting next to a woman who is not his wife.

I often use public transportation scenarios in equanimity meditation. I have a seat on a train. How do I feel if my BFF gets on and sits next to me? If an acquaintance I don't know much about takes that seat? If that talky, conservative co-worker gets it, or some smelly person?

My practice is about being OK with who other people are, not avoiding them. Seeing our shared humanity, even if we display it differently. Recognizing that we're all fighting our own battles and declining to escalate the war. Trying for tolerance and compassion -- and when I fail, knowing that I can keep trying, that small corrections lead to big changes.

Testing the theory of "subliminal priming," researchers found that introducing language associated with Buddhism decreased explicit prejudice against ethnic, ideological, and moral groups other than those of the person. The results challenge the idea that religion promotes prosocial behavior among its members but prejudice toward those outside the group, the authors said. Prosocial behaviors include having compassion and empathy, along with a sense of responsibility for others.

That doesn't mean Buddhism is better, the authors stressed.

"What we really want to argue is that Buddhist concepts are associated with tolerance, across cultural groups," Magalli Clobert, a post-doctoral student at Stanford and one of the study's authors, told The Huffington Post. "It means that, at least in people's mind, there is a positive vision of Buddhism as a religion of tolerance and compassion."My immediate reaction is to list places where that's not true, a compendium of Buddhist behaving badly. That stems, in part, from my Buddhist training -- question everything, especially blanket perceptions. Ask yourself, when those perceptions arise: Is this true? Is it always true? Are there exceptions? Is this solid and permanent? Nope.

But after holding it for a while, I've decided that it's not untrue, either.

One of the beauties of Buddhism is that the Buddha doesn't mandate tolerance. He says, look into yourself and see what makes you intolerant. What makes you uncomfortable? Examine that -- if it is because the person is different, can you find areas of similarity? You both breathe, for starters. You both want to continue breathing. You both love things, maybe different things, but that feeling of love is the same. You're both humans in a confusing world. There's a common ground to start with, and if you dislike what the other person builds on that, you've still got that starting place to come back to so you can tolerate what does not harm your or the larger community and treat the other person with respect if you engage with them over their actions.

I saw this when I read a New York Times story about a woman who was asked to change her seat on an airplane because the man assigned to the seat next to her, an Orthodox Jew, was prohibited by his religion from sitting next to a woman who is not his wife.

I often use public transportation scenarios in equanimity meditation. I have a seat on a train. How do I feel if my BFF gets on and sits next to me? If an acquaintance I don't know much about takes that seat? If that talky, conservative co-worker gets it, or some smelly person?

My practice is about being OK with who other people are, not avoiding them. Seeing our shared humanity, even if we display it differently. Recognizing that we're all fighting our own battles and declining to escalate the war. Trying for tolerance and compassion -- and when I fail, knowing that I can keep trying, that small corrections lead to big changes.

Labels:

buddhism,

buddhist reputation,

compassion,

equanimity,

tolerance

Tuesday, April 7, 2015

You can't win meditation

We're entering heavy sports season here in the U.S., with the

month-long college basketball championships wrapping up -- March Madness

that now extends into April -- and playoffs looming for professional basketball and hockey, even as baseball opened its season Monday.

In a world where ambiguity muddies most situations, sports offer blessed certainty: Someone wins and someone loses. There's comfort in that. (Of course, if you look into the elements that go into those wins and losses, it can get fuzzy. Someone used performance-enhancing drugs. Someone violated recruiting rules.)

We'd like to be able to apply that certainty in our lives -- remember when Charlie Sheen

popularized the "Winning" as a description of his life -- but life's not like that. You could see it as a series of games, I suppose, but there's no championship to end the season, declare a winner, and let everyone go home to rest. Life is about getting up and doing it again.

We'd really like to bring the game dynamic to our meditation practice -- we'd like a score, a quantifiable result that says we've won (or at least made the shot, hit the pitch, touched the rim).

The 17th Karmapa, who's touring the U.S. for three months, touched on this attitude in a talk over the weekend. Asked about ngondro, the preliminary practices students of Tibetan Buddhism undertake to get ready for vajrayana practices, Karmapa noted that attention tends to focus on the uncommon practices: 100,000 prostrations, 100,000 purifications mantras, 1 million or more devotional mantras. Students like to count, he said. Numbers make them feel like they've achieved something.

But in truth, it's the common practices, the ones that don't require any particular initiations, that are most important, Karmapa said. Those include contemplations of the Four Reminders that turn the mind to the dharma: Precious human birth, impermanence, karma, and the suffering inherent in all six realms of samsara.

The problem with those contemplations is that there's no way to quantify the results, Karmapa said. Your mind and your personality improve through those contemplations, he said. But there's no score, no stat line, no trophy that tells you that you've done it right or that you're the best in the league at appreciating your precious human birth, you know impermanence better than anyone. There's just you and those around you experiencing how you live your life.

We find that "boring," Karmapa said, interrupting his translator to say that precise English word. (He speaks in Tibetan, but he occasionally corrects his English translators.)

Those who play sports, who aren't just fans following the hot team, know the truth of what he says, though. Games aren't about the score -- they're about the practices, about building muscle memory so that the body knows what to do. Breanna Stewart doesn't have time in a game to think, now I'm going to block that shot by jumping up; she's well-trained and reacts. Games are about showing up for every play, being present in the moment, no matter what the score. If you're focused more on the score than on the play, you'll screw up and let the opponent win. You need, as the sports cliche says, to keep your head in the game -- and out of dreaming about the victory trip to Disney World.

In shamata meditation, each breath is the only breath. In walking meditation, each step is the only step. In ngondro, every prostration is the only one. Each day starts fresh with no score.

Maybe someday, as secular meditation becomes more popular, there will be meditation competitions and there will be a meditation champion, just as there are yoga competitions now. But there is no outside acclamation or accumulation that can tell you when you're doing it right or doing it better than everyone else.

You'll know you're winning at meditation when that no longer matters.

In a world where ambiguity muddies most situations, sports offer blessed certainty: Someone wins and someone loses. There's comfort in that. (Of course, if you look into the elements that go into those wins and losses, it can get fuzzy. Someone used performance-enhancing drugs. Someone violated recruiting rules.)

We'd like to be able to apply that certainty in our lives -- remember when Charlie Sheen

popularized the "Winning" as a description of his life -- but life's not like that. You could see it as a series of games, I suppose, but there's no championship to end the season, declare a winner, and let everyone go home to rest. Life is about getting up and doing it again.

We'd really like to bring the game dynamic to our meditation practice -- we'd like a score, a quantifiable result that says we've won (or at least made the shot, hit the pitch, touched the rim).

The 17th Karmapa, who's touring the U.S. for three months, touched on this attitude in a talk over the weekend. Asked about ngondro, the preliminary practices students of Tibetan Buddhism undertake to get ready for vajrayana practices, Karmapa noted that attention tends to focus on the uncommon practices: 100,000 prostrations, 100,000 purifications mantras, 1 million or more devotional mantras. Students like to count, he said. Numbers make them feel like they've achieved something.

But in truth, it's the common practices, the ones that don't require any particular initiations, that are most important, Karmapa said. Those include contemplations of the Four Reminders that turn the mind to the dharma: Precious human birth, impermanence, karma, and the suffering inherent in all six realms of samsara.

The problem with those contemplations is that there's no way to quantify the results, Karmapa said. Your mind and your personality improve through those contemplations, he said. But there's no score, no stat line, no trophy that tells you that you've done it right or that you're the best in the league at appreciating your precious human birth, you know impermanence better than anyone. There's just you and those around you experiencing how you live your life.

We find that "boring," Karmapa said, interrupting his translator to say that precise English word. (He speaks in Tibetan, but he occasionally corrects his English translators.)

Those who play sports, who aren't just fans following the hot team, know the truth of what he says, though. Games aren't about the score -- they're about the practices, about building muscle memory so that the body knows what to do. Breanna Stewart doesn't have time in a game to think, now I'm going to block that shot by jumping up; she's well-trained and reacts. Games are about showing up for every play, being present in the moment, no matter what the score. If you're focused more on the score than on the play, you'll screw up and let the opponent win. You need, as the sports cliche says, to keep your head in the game -- and out of dreaming about the victory trip to Disney World.

In shamata meditation, each breath is the only breath. In walking meditation, each step is the only step. In ngondro, every prostration is the only one. Each day starts fresh with no score.

Maybe someday, as secular meditation becomes more popular, there will be meditation competitions and there will be a meditation champion, just as there are yoga competitions now. But there is no outside acclamation or accumulation that can tell you when you're doing it right or doing it better than everyone else.

You'll know you're winning at meditation when that no longer matters.

Saturday, March 28, 2015

When life gives you mushy peas

As a child I was often told that starving children in China would be happy to have the mushy peas I carefully picked out from the Campbell's vegetable soup and left in the bowl. I felt bad for the starving children and guilty, but that wasn't going to make me like the mushy peas -- or the occasional lima beans that kept them company after everything else was gone.

I thought of that this week because of a couple of unexpected events that caused some strong shifts in the family Force. Nothing awful -- a car given a terminal diagnosis, a recurring expense that the new health insurance covers far less of than the previous policy. Unexpected. Unpleasant. Inconvenient. But not tragic.

It's interesting to watch where your mind goes when the earth shifts. There's a moment when you feel it, and then the mind starts to scramble. Uneven ground is uncomfortable. So the mind seeks level ground again. It looks for someone to blame -- or absorbs the blame itself. What was done? What was not done? Who did or didn't do it? What should have been done? What should happen now? What might happen next? Can I ignore it? Pretend it didn't happen? Assure myself it isn't important -- after all, there are children starving somewhere, buildings exploding, wars being fought, and I'm upset about a car.

And while there's value in putting our suffering into perspective, I think it's important to acknowledge the shock to the system, to be disconcerted, surprised, and confused. To accept the feelings that arise before deciding they're inappropriate.

Knowing that other people have it worse, that my problems are mushy peas while others deal with massive boulders, can convince me to disallow my feelings. And I fear I'm even worse when I'm dealing with other people's feelings. I want them to feel OK, and I may jump into telling them why they're OK before letting them be not OK with what's happening.

But the feeling isn't really about the car; it's about the loss, about change, about impermanence. It's a reminder of the inevitable breakdown of everything, the truth of impermanence. And that's universal. It's a connection with all of the humans who are discovering that. Change is scary, loss hurts. Touching that in myself opens me up to touching it in others; denying it in myself, even if it's because I see it as less legitimate than others' pain, closes me off to all of it.

It's OK to hate the mushy peas, even if someone else would like them or is so hungry that they'd appreciate them even if they didn't like the taste or texture. Let those feelings remind you that everybody is faced with things they don't much like to varying degrees -- and make the aspiration that all beings have good things that bring them happiness, that all beings don't have the things that bring them unhappiness, and that all beings have the equanimity to sit with both.

And do what you can to share what you have. Donate to a food bank. Hold a friend's sadness with love before cheering them up. Don't tell a serious-faced person to smile -- just smile at them.

I thought of that this week because of a couple of unexpected events that caused some strong shifts in the family Force. Nothing awful -- a car given a terminal diagnosis, a recurring expense that the new health insurance covers far less of than the previous policy. Unexpected. Unpleasant. Inconvenient. But not tragic.

It's interesting to watch where your mind goes when the earth shifts. There's a moment when you feel it, and then the mind starts to scramble. Uneven ground is uncomfortable. So the mind seeks level ground again. It looks for someone to blame -- or absorbs the blame itself. What was done? What was not done? Who did or didn't do it? What should have been done? What should happen now? What might happen next? Can I ignore it? Pretend it didn't happen? Assure myself it isn't important -- after all, there are children starving somewhere, buildings exploding, wars being fought, and I'm upset about a car.

And while there's value in putting our suffering into perspective, I think it's important to acknowledge the shock to the system, to be disconcerted, surprised, and confused. To accept the feelings that arise before deciding they're inappropriate.

Knowing that other people have it worse, that my problems are mushy peas while others deal with massive boulders, can convince me to disallow my feelings. And I fear I'm even worse when I'm dealing with other people's feelings. I want them to feel OK, and I may jump into telling them why they're OK before letting them be not OK with what's happening.