As a child I was often told that starving children in China would be happy to have the mushy peas I carefully picked out from the Campbell's vegetable soup and left in the bowl. I felt bad for the starving children and guilty, but that wasn't going to make me like the mushy peas -- or the occasional lima beans that kept them company after everything else was gone.

I thought of that this week because of a couple of unexpected events that caused some strong shifts in the family Force. Nothing awful -- a car given a terminal diagnosis, a recurring expense that the new health insurance covers far less of than the previous policy. Unexpected. Unpleasant. Inconvenient. But not tragic.

It's interesting to watch where your mind goes when the earth shifts. There's a moment when you feel it, and then the mind starts to scramble. Uneven ground is uncomfortable. So the mind seeks level ground again. It looks for someone to blame -- or absorbs the blame itself. What was done? What was not done? Who did or didn't do it? What should have been done? What should happen now? What might happen next? Can I ignore it? Pretend it didn't happen? Assure myself it isn't important -- after all, there are children starving somewhere, buildings exploding, wars being fought, and I'm upset about a car.

And while there's value in putting our suffering into perspective, I think it's important to acknowledge the shock to the system, to be disconcerted, surprised, and confused. To accept the feelings that arise before deciding they're inappropriate.

Knowing that other people have it worse, that my problems are mushy peas while others deal with massive boulders, can convince me to disallow my feelings. And I fear I'm even worse when I'm dealing with other people's feelings. I want them to feel OK, and I may jump into telling them why they're OK before letting them be not OK with what's happening.

But the feeling isn't really about the car; it's about the loss, about change, about impermanence. It's a reminder of the inevitable breakdown of everything, the truth of impermanence. And that's universal. It's a connection with all of the humans who are discovering that. Change is scary, loss hurts. Touching that in myself opens me up to touching it in others; denying it in myself, even if it's because I see it as less legitimate than others' pain, closes me off to all of it.

It's OK to hate the mushy peas, even if someone else would like them or is so hungry that they'd appreciate them even if they didn't like the taste or texture. Let those feelings remind you that everybody is faced with things they don't much like to varying degrees -- and make the aspiration that all beings have good things that bring them happiness, that all beings don't have the things that bring them unhappiness, and that all beings have the equanimity to sit with both.

And do what you can to share what you have. Donate to a food bank. Hold a friend's sadness with love before cheering them up. Don't tell a serious-faced person to smile -- just smile at them.

Saturday, March 28, 2015

Friday, March 20, 2015

The lotus and the mud

You often see lotuses in images of Eastern religions or philosophies. They stand for beauty, peace, purity -- in Tibetan Buddhist iconography, the buddhas sit on lotuses with as many as 100,000 petals, symbolic of their great wisdom and compassion.

But lotuses, as lovely as they are, grow in unlovely mud, not pristine pools. They live in the mud and the muck; they thrive there. They don't transcend the mud. They exist together, inseparable. As Thich Naht Hanh says, they inter-are. No mud, no lotus.

Merriam-Webster defines transcendent as "going beyond ordinary experience." But Buddhism celebrates the ordinary as the path to liberation. Zen teacher Charlotte Joko Beck started the lineage of Ordinary Mind Zen. Popular teacher Pema Chodron advises us to "start where you are." You work with what you have -- emotions, fears, irritations, pleasures -- and use that to wake up to the way habitual patterns rule your life and keep your from directly experiencing the world. "When nothing is special, everything can be," Beck writes.

Our tendency is to avoid those feelings, to pretend the lotus exists independently of the mud. That leads to suffering, as we blindly follow habits, doing the same things over and over to distract ourselves and wondering why it doesn't make us feel good. Buddhist psychologist John Welwood coined the term "spiritual bypassing," which refers to that tendency to use spiritual practices and beliefs to avoid dealing with the discomfort of life. Denying suffering or bypassing it without examining it, processing it, loving it, leaves it there, and you're likely to find yourself back there.

The Buddha taught that nirvana -- or liberation -- is not separate from samsara, the world of habit and struggle. They exist together, like the mud and the lotus. It's about all in how you see and understand it. If we see the mud as an unacceptable, unpleasant aspect of life that needs to be cleaned up or covered over, we're creating suffering, trying to do what can't be done. If we accept it, we can appreciate fully the beauty of the lotus.

But lotuses, as lovely as they are, grow in unlovely mud, not pristine pools. They live in the mud and the muck; they thrive there. They don't transcend the mud. They exist together, inseparable. As Thich Naht Hanh says, they inter-are. No mud, no lotus.

Merriam-Webster defines transcendent as "going beyond ordinary experience." But Buddhism celebrates the ordinary as the path to liberation. Zen teacher Charlotte Joko Beck started the lineage of Ordinary Mind Zen. Popular teacher Pema Chodron advises us to "start where you are." You work with what you have -- emotions, fears, irritations, pleasures -- and use that to wake up to the way habitual patterns rule your life and keep your from directly experiencing the world. "When nothing is special, everything can be," Beck writes.

Our tendency is to avoid those feelings, to pretend the lotus exists independently of the mud. That leads to suffering, as we blindly follow habits, doing the same things over and over to distract ourselves and wondering why it doesn't make us feel good. Buddhist psychologist John Welwood coined the term "spiritual bypassing," which refers to that tendency to use spiritual practices and beliefs to avoid dealing with the discomfort of life. Denying suffering or bypassing it without examining it, processing it, loving it, leaves it there, and you're likely to find yourself back there.

The Buddha taught that nirvana -- or liberation -- is not separate from samsara, the world of habit and struggle. They exist together, like the mud and the lotus. It's about all in how you see and understand it. If we see the mud as an unacceptable, unpleasant aspect of life that needs to be cleaned up or covered over, we're creating suffering, trying to do what can't be done. If we accept it, we can appreciate fully the beauty of the lotus.

Labels:

john welwood,

joko beck,

lotus,

no lotus,

no mud,

pema chodron,

spiritual bypassing,

transcendence

Sunday, March 15, 2015

Bearing witness to the body

We create the world with our thoughts, the Buddha taught, but we experience it with our bodies. That's one of those fun conundrums of Buddhism.

It's an issue I work with a lot, particularly since my practice now involves visualizations. How do I keep from becoming a brain on a stick, a mind that observes sensations without feeling them? Where is my body if my mind is projecting the consciousness elsewhere?

Ruth Denison, a Buddhist teacher who expanded the teachings on mindfulness of the body, describes its value like this:

It's an issue I work with a lot, particularly since my practice now involves visualizations. How do I keep from becoming a brain on a stick, a mind that observes sensations without feeling them? Where is my body if my mind is projecting the consciousness elsewhere?

Ruth Denison, a Buddhist teacher who expanded the teachings on mindfulness of the body, describes its value like this:

It is tangible right away, it makes sense, it is giving a bridge to modern physics, to modern science, and it gives you a personal touch with yourself. It is all spiritual and enlightenment. So it was not something to believe in or to bow to,you didn't need to pray to it. It brought me into daily life, where I know that everything is having this impermanence.Denison, who studied body awareness before coming to Buddhist teacher U Ba Khin, describes the process with exquisite awareness, in her biography, Dancing in the Dharma:

When I breathe in and feel a deeper breath and allow that, then I feel a relationship between the breath energy and the body energy. The breath moves into the body and changes the sensations, that aliveness, and it is recharged with the in breath. Then it goes out and comes in again. I also discovered that when I am allowing more deeply the breathing that I have deeper access to the body sensations, because I can witness or feel that every part of the body is in my attention, like it is enlivened with the breath. It is always so, but now because of my attention I could experience that directly. So it was not anymore anything I have to worship or ask how to understand. I just thought, 'Aha, this is this.'Denison's witness is embodied, engaged, embedded in her being. It's not sitting by, watching the breath flow by -- it is feeling it, down to the exchange of oxygen between the breath and blood. And in that observation of the smallest details, the whole of the universe is revealed.

Saturday, March 7, 2015

Ruth Denison, Dharma Elder

I've been reading about Ruth Denison, a Buddhist teacher who died Feb. 26. I'd picked up a book about her, Dancing in the Dharma, because I liked the title. I had not heard of her. That's a shame, because Denison's work deeply influenced how Buddhism is taught in the west.

I'm deeply grateful for her work, even though I didn't know it was her work, that it wasn't always this way. I don't think I'm alone in that -- her Wikipedia entry is seven sentences.

Denison was among the first wave of westerners who went east, a contemporary of Jack Kornfield, Sharon Salzberg, and others whose work formed the bones of Insight Meditation. She taught at their centers, at Spirit Rock and Insight Meditation Society, but in her own idiosyncratic way. She was not popular with students who wanted a traditional experience, Salzberg says in the book.

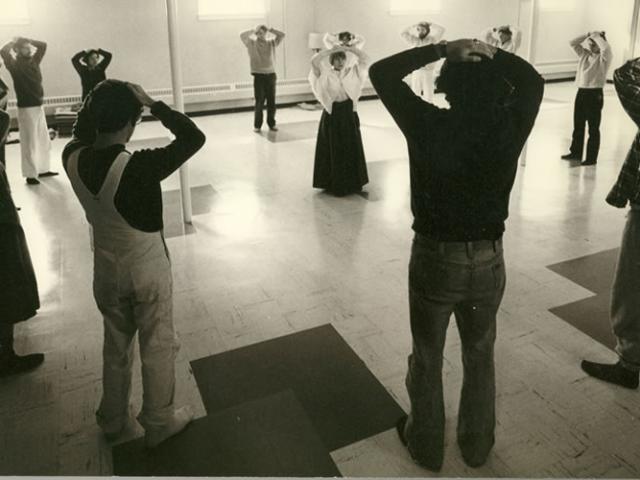

Denison's gift to the dharma and its students was to introduce and integrate body practices. Having studied in Zen before finding her teacher in U Ba Khin, she taught walking meditation. She taught students to ground in their bodies, to use sensation to integrate body and mind. When her contemporaries were experimenting with psychedelics and meditation, Denison was known as a person who could help those having a bad trip by keeping them anchored in their bodies. After she opened a dharma center, Dhamma Dena, she was known as a teacher who could work with students who had mental illness or other difficulties.

She also worked with women, creating the first retreat for women practitioners, and brought a strong feminine presence to Buddhism.

Dancing in the Dharma is written by one of Denison's longtime students, but it's unusually clear-eyed and straight forward, not sentimental or cloying. In that, it seems to be a fair reflection of Denison. She had a fascinating life, growing up in Germany between the wars, living through horrific experiences, and coming west to join the counter culture and then Buddhism. But she seems not have been particularly impressed by any of it, going about her life.

I'm deeply grateful for her work, even though I didn't know it was her work, that it wasn't always this way. I don't think I'm alone in that -- her Wikipedia entry is seven sentences.

Denison was among the first wave of westerners who went east, a contemporary of Jack Kornfield, Sharon Salzberg, and others whose work formed the bones of Insight Meditation. She taught at their centers, at Spirit Rock and Insight Meditation Society, but in her own idiosyncratic way. She was not popular with students who wanted a traditional experience, Salzberg says in the book.

Denison's gift to the dharma and its students was to introduce and integrate body practices. Having studied in Zen before finding her teacher in U Ba Khin, she taught walking meditation. She taught students to ground in their bodies, to use sensation to integrate body and mind. When her contemporaries were experimenting with psychedelics and meditation, Denison was known as a person who could help those having a bad trip by keeping them anchored in their bodies. After she opened a dharma center, Dhamma Dena, she was known as a teacher who could work with students who had mental illness or other difficulties.

She also worked with women, creating the first retreat for women practitioners, and brought a strong feminine presence to Buddhism.

Dancing in the Dharma is written by one of Denison's longtime students, but it's unusually clear-eyed and straight forward, not sentimental or cloying. In that, it seems to be a fair reflection of Denison. She had a fascinating life, growing up in Germany between the wars, living through horrific experiences, and coming west to join the counter culture and then Buddhism. But she seems not have been particularly impressed by any of it, going about her life.

In her teaching and in her life, Ruth acts spontaneously; she is so fully committed to this moment that she may lose track of what she promised yesterday, or even the prescribed schedule of events at a retreat. At first this evoked little fits of exasperation in me -- until I discovered the obvious, that it was my own mind that was causing me to suffer. Then I began to understand that this was a great teaching for me: to get go of expectations, to not hold so tightly to my own precious agenda, to break the form and stay with the interest and joy of the present moment. -- Sandy Boucher, Dancing in the Dharma

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)