The first time I saw

Oprah Winfrey, who has a

net worth of $2.9 billion, promoting mindfulness on the cover of O! Magazine, I was taken aback. I was fairly new to Buddhist studies then, and I was protective of the dharma. How did mindfulness -- the practice of recognizing what's going on in the present moment and noting the distractions of desire and despair as they arose -- fit with a magazine that promoted buying pretty things to make yourself happier? (O! highlights a monthly list of things Oprah likes -- that I could never afford.)

But Oprah persisted, and I made my peace with it. She

introduced hundreds of thousands to Buddhist nun

Pema Chodron's teachings and featured other Buddhist teachers along with fashion and food. Any increase in mindfulness is of benefit, I told myself.

But now I wonder whether that's true.

We're in the midst of a

"Mindful Revolution," according to Time magazine, and mindfulness proliferates -- there are publications devoted to mindful money, schools, and eating. There's dozens of studies confirming its benefits: lower blood pressure, brain changes, improvements in immune system function, decreased symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and on and on. Much of the research looks at

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, a program developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn at Harvard Medical School.

This is mindfulness divorced from Buddhist teachings on ethics and the development of wisdom. This is knowing what

is without insight about how it came to be and how it might be different. (Josh Korda

explains this aspect.)

Questions have been raised in several forums lately about whether mindfulness -- which so far has been found to have only beneficial effects on individuals' health and well being -- might be detrimental to society when separated from other aspects of spiritual development.

In an essay called

"The Mindfulness Racket" Evgeny Morozov posits that mindfulness is being used to reinforce the status quo, especially among tech companies whose leaders now advocate for technology detoxes. He writes:

No wonder (Ariana) Huffington hopes that the pursuit of mindfulness can finally

reconcile spirituality and capitalism. “There is a growing body of

scientific evidence that shows that these two worlds are, in fact, very

much aligned — or at least that they can, and should, be,” she wrote in a recent column.

“So yes, I do want to talk about maximizing profits and beating

expectations — by emphasizing the notion that what’s good for us as

individuals is also good for corporate America’s bottom line.”

Ironically, perhaps, he concludes by urging mindful use of mindfulness -- know why we're doing what we're doing, whether it's to be more rested and productive or to undermine the effects of technology promoted by the corporations. (In a further irony, there are ads for "sound meditation" interspersed in the article.)

On Salon, in an article called

"Gentrifying the Dharma: How the 1% is Co-Opting Mindfulness," Joshua Eaton writes:

Corporate America has embraced mindfulness as a way to raise bottom

lines without raising blood pressure — much to the chagrin of people ... who feel that Buddhism’s message is much more radical.

Eaton quotes Marxist philosopher Slavoj

Žižek, who he says "has long argued that 'Western Buddhism,' as he calls it, is an

ideal palliative for the stresses of life under late capitalism — their

'perfect ideological supplement.'

“It enables you to fully participate in the frantic pace of the capitalist game,” Žižek explains in a 2001 essay for Cabinet magazine,

“while sustaining the perception that you are not really in it; that

you are well aware of how worthless this spectacle is; and that what

really matters to you is the peace of the inner Self to which you know

you can always withdraw.”

Several major corporations offer mindfulness programs to their employees, including Google, Coca-Cola, and General Mills.

It was Google, in fact, that sparked much of the recent discussion of the role of mindfulness. At the Google-sponsored Wisdom 2.0 conference, protesters disrupted a panel of speakers from Google with charges that the company may be mindful but it's lacking in compassion.

One of the protesters, Amanda Ream, wrote about it in

a blog post for Tricycle Magazine:

“Most of the workshops offer lifestyle and consumer choices that are

meant to help people heal from the harm, emptiness and unsustainability

associated with living under capitalism, but [they do so] without

offering an analysis of where this disconnection comes from. ... “The conference presents

an evolution in consciousness of the wealthiest among us as the antidote

to suffering rather than the redistribution of wealth and power.”

Aetna CEO

Mark Bertolini is a meditator and yoga practitioner who's used his bully pulpit to

Bertolini announced a partnership between Aetna and actress

Goldie Hawn designed to expand a school-based stress reduction program called MindUP that’s sponsored by The Hawn Foundation.

promote mindfulness. At the recent World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, on a panel led by Arianna Huffington,

A month later, Bertolini announced Aetna's annual profits: $1.9 billion for 2013.

How does a company mindfully spend $1.9 billion? It seems that it primarily rewards its stockholders -- and promises to continue doing so.

But corporations aren't people. They don't have hearts or minds. And corporations aren't necessarily mindful, even if they are filled with calm, compassionate workers who are present for each other and their customers. For all the good it may do to have happy workers, if they're functioning in a larger system that values profit over people, the value is limited.

In

Salon, Curtis White and Andrew Cooper write about the contradictions between Buddhism and business.

In the literature of mindfulness as stress reduction for business, we’ve

seen no suggestion that employees ought to think about — be mindful of —

whether they or the company they work for practice right livelihood.

Corporate mindfulness takes something that has the capacity to be

oppositional, Buddhism, and redefines it. Mindfulness becomes just

another aspect of “workforce preparation.” Eventually, we forget that it

ever had its own meaning.

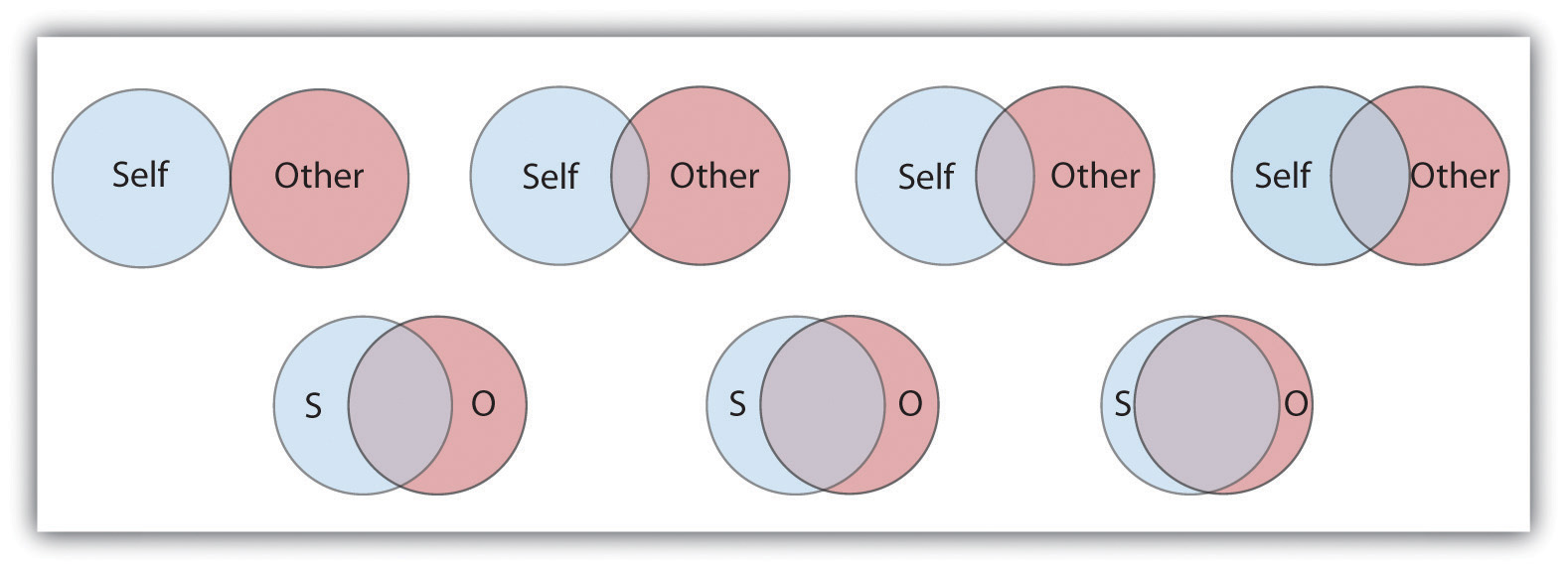

The question is no longer whether mindfulness is good or whether it can find wider acceptance. The question is whether individuals can move from awareness of their own present moment to the their company's moment and to society's moment -- and how those are interdependent.

It takes wisdom and ethics, not just mindfulness, to make societal change.

Sociologist

C. Wright Mills wrote in 1962:

If you do not specify and confront real issues, what you say will surely

obscure them. If you do not embody controversy, what you say will be an

acceptance of the drift to the coming human hell.

Meditation is our way of identifying and seeing those issues. Acting with wisdom and skill, born of ethics, is how we change the drift of society so that it is headed away from individualistic and profane to enlightenment.