Shinzen Young, a secular Buddhist, says that the word equanimity comes from the Latin word aequus, meaning balanced, and animus, meaning spirit or inner state. So it means a balanced inner state.

Shinzen, who takes a scientific approach to Buddhist teachings, offers a number of physical analogies for equanimity:

Reducing friction in a mechanical system.

Reducing viscosity in a hydrodynamic system

Reducing resistance in a DC circuit

Reducing impedance in an AC circuit

Reducing stiffness in a spring.

When we have equanimity, he says, emotions flow through us, rather than getting stuck, which allows us to be with them without getting obsessed or fixated.

More poetically, Gil Fronsdal describes equanimity as “one of the most sublime emotions of Buddhist practice. It is the ground for wisdom and freedom and the protector of compassion and love. While some may think of equanimity as dry neutrality or cool aloofness, mature equanimity produces a radiance and warmth of being. The Buddha described a mind filled with equanimity as “abundant, exalted, immeasurable, without hostility, and without ill-will.”

Fronsdal says there are two Pali words that are often translated as equanimity, which reveal two aspects of it. (Pali is the language of the earliest Buddhist texts).

The first is upekkha, meaning “to look over.” It refers to the equanimity that arises from the power of observation, the ability to see without being caught by what we see. When well-developed, such power gives rise to a great sense of peace. It’s also translated as “to see with patience,” such as when we listen to criticism without getting defensive, or “grandmotherly love.”

The second meaning is literally “to stand in the middle of all this.” Fronsdal says that “being in the middle” refers to balance, to remaining centered in the middle of whatever is happening. This balance comes from inner strength or stability. The strong presence of inner calm, well-being, confidence, vitality, or integrity can keep us upright, like a ballast keeps a ship upright in strong winds. As inner strength develops, equanimity follows.”

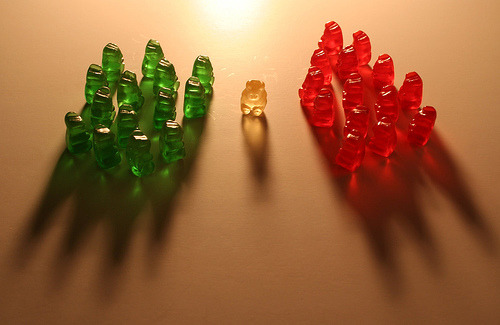

Equanimity works with what the Buddha called the Eight Worldly Winds. They’re four pairs of states that represent the extreme points of a pendulum’s swing: Praise and blame, fame and ill-repute, success and failure, pleasure and pain. Often we classify our experiences as one or the other. We rarely sit exactly in between them – but that’s where equanimity (and sanity) lie.

My guess is that we can all agree this sounds like a good thing. It’s the eye of the storm, the ability to keep your head when everyone else is losing theirs.

Buddhism is a practical path, so how do we get there?

To some degree, equanimity is what’s known as a fruitional quality – the result of other practices. It is the fourth of the Four Brahma Viharas, or immeasurable states, and said to be the most difficult to attain. To dwell in equanimity, you have to accept impermanence and emptiness – the current situation, whatever it is, will not last. Nor will it define us. Emptiness says that states of being (and beings) are not solid, permanent, or independent. We change in response to circumstances; we adapt; we persevere. Life goes on.

We lose equanimity, and resilience, when we think that a situation has to be a certain way to be acceptable, that we can’t go on without whatever thing or circumstance we think is necessary. Then we suffer. If we can be flexible and work with what we have rather than insisting that things be a certain way, we can come back into balance.

We can experience this in meditation. When we lose concentration and get distracted, we come back. When the room is too hot or too cold, too loud, too quiet, with too many people or not enough, we watch thoughts arise and pass, pains arise and diminish, and emotions move through our minds like clouds across the sky. The sky is there no matter what is front of it – and when the clouds move or the storm clears or the bright sun sets, there it is. It doesn’t come back; it was always there, just obscured. Equanimity is always there; we just have to cultivate it and learn to access it.

Shinzen Young suggest specific ways to create equanimity in your mind and body in meditation:

Let's say that you have a strong sensation in one part of your body. As you focus attention on what is happening over your whole body, you notice that you are tensing your jaw, clenching your fists, tightening your gut, and squnching your shoulders. Each time you become aware of tensing in some area, you intentionally relax it to whatever degree possible. A moment later you may notice that the tensing has started again in some area; once again gently relax it to whateverHe also suggests we notice when we spontaneously fall into equanimity. By

degree possible. If there are areas that cannot be relaxed much or at all, you try to accept the tension sensations and just observe them.

As a result of maintaining this whole-body relaxed state, you may begin to notice subtle flavors of sensation spreading from the local area of intensity and coursing through your body. These are the sensations that you had been masking by tension. Now that they have been uncovered, try to create a mental attitude of welcoming them, not judging them. Observe them with gentle matter-of-factness, giving them permission to dance their dance, to flow as they wish through your body.

becoming familiar with it, we can extend it.

Pema Chodron says the traditional image for equanimity is a banquet to which everyone is invited. “Training in equanimity is learning to open the door to all ... inviting life to come visit,” she writes.

To cultivate equanimity, we practice catching ourselves when we feel attraction or aversion, before it hardens into grasping or negativity. She suggests training in equanimity by walking down the sidewalk, or through the mall, and noticing our feelings about each person we pass. We can use those feelings to develop empathy and compassion. Does that person look crabby? Sometimes I’m crabby too – can I make a mental wish for them to be happy? Do they look friendly? What feelings come up in us?

“When we have a feeling of spaciousness and ease that’s not caught up in preference or prejudice, that’s equanimity,” she says.

Traditionally, equanimity is developed by cultivating the seven factors that support it. Fronsdal describes them this way:

-- The first is virtue or integrity. When we live and act with integrity, we feel confident about our actions and words, which results in the equanimity of blamelessness. The ancient Buddhist texts speak of being able to go into any assembly of people and feel blameless.

--The second support for equanimity is the sense of assurance that comes from faith. While any kind of faith can provide equanimity, faith grounded in wisdom is especially powerful. The Pali word for faith, saddha, is also translated as conviction or confidence. If we have confidence, for example, in our ability to engage in a spiritual practice, then we are more likely to meet its challenges with equanimity.

--The third support is a well-developed mind. Much as we might develop physical strength, balance, and stability of the body in a gym, so too can we develop strength, balance and stability of the mind. This is done through practices that

cultivate calm, concentration and mindfulness. When the mind is calm, we are less likely to be blown about by the worldly winds.

--The fourth support is a sense of well-being. We do not need to leave well-being to chance. In Buddhism, it is considered appropriate and helpful to cultivate and enhance our well-being. We often overlook the well-being that is easily available in daily life. Even taking time to enjoy one’s tea or the sunset can be a training in well-being.

--The fifth support for equanimity is understanding or wisdom. Wisdom is an important factor in learning to have an accepting awareness, to be present for whatever is happening without the mind or heart contracting or resisting. Wisdom can teach us to separate people’s actions from who they are. We can agree or disagree with their actions, but remain balanced in our relationship with them. We can also understand that our own thoughts and impulses are the result of impersonal conditions. By not taking them so personally, we are more likely to stay at ease with their arising.

Another way wisdom supports equanimity is in understanding that people are responsible for their own decisions, which helps us to find equanimity in the face of other people’s suffering. We can wish the best for them, but we avoid being buffeted by a false sense of responsibility for their well-being.

One of the most powerful ways to use wisdom to facilitate equanimity is to be mindful of when equanimity is absent. Honest awareness of what makes us imbalanced helps us to learn how to find balance.

--The sixth support is insight, a deep seeing into the nature of things as they are. One of the primary insights is the nature of impermanence. In the deepest forms of this insight, we see that things change so quickly that we can’t hold onto anything, and eventually the mind lets go of clinging. Letting go brings equanimity; the greater the letting go, the deeper the equanimity.

--The final support is freedom, which comes as we begin to let go of our reactive tendencies. We can get a taste of what this means by noticing areas in which we were once reactive but are no longer. For example, some issues that upset us when we were teenagers prompt no reaction at all now that we are adults. In Buddhist practice, we work to expand the range of life experiences in which we are free.

Shinzen says:

Equanimity belies the adage that you cannot “have your cake and eat it too.” When you apply equanimity to unpleasant sensations, they flow more readily and as a result cause less suffering. When you apply equanimity to pleasant sensations, they also flow more readily and as a result deliver deeper fulfillment.

Shinzen Young, What is Equanimity?

Gil Fronsdal, Equanimity

Pema Chodron, The Places that Scare You: A guide to fearlessness in difficult times

No comments:

Post a Comment